It has been years since last Bahram slept. Sleep had become a horror, and nightmares snake up from the darkness of night to snap at dreams. As darkness closed in about him, he would see again that shocked face, and the mad creatures who leapt upon it, tearing and screaming in their barbaric Oghuz, in sadistic exultation. He would freeze again, as the voices about him circled again, cheering and laughing. Then, his whole body would shake, and he would light again the lamp he has doused five, perhaps ten times already. No, no, there was no time to rest. There never was. Better to at last rise again, from where he lay still as the dead, and again wander as he would always, in the vacated streets after even the robbers have gone to their beds.

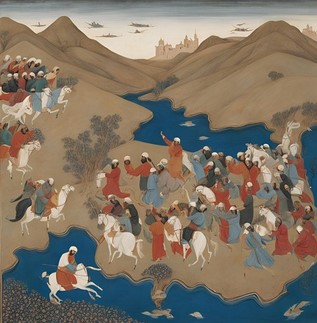

Wandering was human. It made him feel human, especially in moments when he did not otherwise. Haxamanish wandered from Parsua to Anshan, Iskandar wandered from Yauna to Marvdasht, the Parthava wandered from Khorasan to Tysfun. Who was Bahram the Aswar to deny this shared nature, and remain idle in his home? So he did, night after night, some nights sharing the company of a wide and glorious moon, some nights alone but for his ailing soul, and all the painful memories that it stubbornly carried. Those nights were often longest, and worse, chilliest. Even on summer nights, the power of his emotion made him shiver and clutch his robe about his shoulders, breathing shallow so as not to inhale and let the air, the freezing sensation, enter into his body again. Gratefully, nights were never eternal, and day would always follow eventually, even in the last days of winter.

Yet the dawn was little comfort, for it reminded him with its grasping arms the face again, that he had no ability nor desire to forget. The man in that image was staring at him through the lens of the sun, still as shocked as he was on that day, but now it was directed at him.

“Why is mighty Bahram so small now?” That face would wonder, without having to speak. “Where is his brother, who shared the womb with him, but stood without that unsightly hunch in his back? Hello! I call upon Bahram’s other face, the one whose beard was combed, the one who rode alongside me once, the one who crashed against the Arab with the strength of three hundred Anushirvans!”

“Please, look away from me,” Bahram would mutter, for he could not help but speak. “Bahram the Aswar lays beside Mardavij Shahanshah, in his court where he fell five years ago. In his footsteps he leaves the corpses of the Oghuz who betrayed him, and those of the schemers Vushmgir Amir and Bajkam Ghulam.” He spoke it, for it was his lie, and a lie would never be believed inside the mind alone.

Even to say the name of Mardavij filled him with the greatest joy that springs only from sorrow. To recall him, even while he lived, was to recall the sun, and nothing lesser. The men of Persia would see him pass, and they would whisper to themselves one name. Saoshyant, they would say. It would follow him as he proceeded, south from Tabaristan below the Mazandaran, down through the Alborz towards Ispahan, and out along the spine of the Zagros to Parsa. Saoshyant, Saoshyant, Sasan reborn again, body of Ziyar and soul of Zarathustra, the Persians would say. The Arabs would spit behind his back, but as he turned to look they trembled and averted their gaze. All knew him east of the Arvand Rud, well or poorly, they knew him nonetheless. He was fire, he was the river, and he was loved by Bahram.

That was the only truth Bahram would keep, if he died as he meant to. The only truth that the rain shall never fall upon, even as the vultures pick apart his heart. Not even Hormazd shall know, and when Ahriman feasts on his unclean remains, he will not taste even a hint of it. He would cut his beard, not missing it, tangled mess that it had become, and leave it behind him in clumps. He will throw his cap on the ground and stomp it into the earth, the detestable thing, and once again take up the sword and the horse, if great Mardavij would but call his name again. He would ride the breadth of Persia, from the Ufratu to the Hindu Kush, from the steppes above Samarkand to the Gulf below, not pausing for a breath if his Shahanshah would only command it. Bahram could recall bravery, somewhat vaguely, but the locus of it was empty. He could not be brave anymore, as he lives now not even half a man, not even a quarter of a man. He has nothing anymore to be brave for.

Tonight, the memory comes stronger than they ever have before. The Oghuz descend down from the sky all at once, like the dutiful vulture, but Mardavij lived still. With their knives and their anger, they hack and tear into their Shahanshah, as he lashes them with his Pahlavi tongue. There he lay, regal in the silver crown that adorned him, untouched in the violence, affixed to his head more loyal than any of his pushtigban, still glittering with the life that had left its bearer.

“Will you not fight for your precious Dhimmi, your dog-lover, your fire worshipper?” Bajkam had said, standing above the corpse, dagger in his hand. None of the aswaran, who once braided their beards tightly and adorned it in jewels, who called themselves Immortal as they postured to each other, none of them would stand to face the traitor. Bahram had little anger for them; he was the same. They all knew that while there may have been thousands of Oghuz, while there have been tens of thousands of Arabs, there was only one Saoshyant, and he was fallen. This was the treachery that could not be unmade, not with the seas of blood they had waded through before, not with a sea of bloodshed the scope of the Indian Ocean. No amount of Arab flesh, cut and cast into the earth, would sate Hormazd that he would return Mardavij back to the living. So they all scattered, slowly over the months, escaping to every corner of the world so long as it was not Persia. Bahram had not seen any one of their faces since that day. They hide theirs as he does, from the sky, wherever in the world they live.

Some of his brothers could never live under the yoke of their ignoble defeat, and fled across the Hindu Kush, to join their cousins on the far side of those impenetrable mountains. They spoke the tongue and wore the garments of their host the Mahipala Shah. Some of them lived on as dhimmi, bearing the yellow belt and shying away at the sight of a muqti. They kept their silver close to their vestments, and feigned poverty when it was time to pay jizya. Some, however, abandoned their pride entirely, alongside their names, laid at the feet of those who wronged them. Bahram detested them, the cowards, for of them he was one. To think, without his light to guide him, he was docile as the Bavands. Like them, he burned righteous in his power. Like them, he submitted in his weakness. As a horse does. As a donkey does.

“Salaam, Bahram the Ayyar,” said a figure on the ground, which shocked Bahram as he gazed towards the sky. Instantly, he rankled against the title. Bahram the Ayyar, the Oghuz would call him, as they became lords and he became nothing. It was a name to mock him, to mark him, to diminish him, that a proud aswar could be demoted to a mere ayyar as soon as the fortunes of the Arab turned against him. It sounded to him an insult. Bahram the Meek, Bahram the Horn-Wearer. Bahram who carried the torch that blazed in his chest, until the fire within it extinguished, and he dropped the cold stick. He turned to face the one who vexed him so suddenly, only to find the shattered remnants of a face he once knew well.

“Salaam, Mazyar the Dhimmi,” Bahram spat. They did not kiss as brothers would. Instead, Mazyar lifted a single eyebrow, as was his habit, and Bahram could see under it an eye as heavy and dead as his own.

“That is as we say it now, yes? ‘Salaam.’ You know better than I.” Mazyar did nothing to hide the indignation in his voice. It was the same contempt Bahram held for himself, but dutiful rather than painful. The two men stood paces apart, but in between them was a world. For all his humiliations, an ayyar was an ayyar still, and a dhimmi was not. Mazyar was ragged as an Afghan, but for the yellow sash that looped about his waist, and Bahram knew that he was jealous. Mazyar would look at him and see his robes that were still well-kept, see the sword that he still wore, but Bahram would look at Mazyar and see the heart that beat steady in its conviction. For all the jizya has been taken from him, for all the temples that have extinguished before him, for all the comrades that have been killed beside him, Mazyar was a Persian still. His heart beat the steady meter of the Gathas defiantly under the screaming call of namaz. He paid dearly with all the wealth he had, but he did not pay with his soul. “Have you any wine to drink?”

“I have not either,” Bahram said, whispering and shaking his head slowly. He had not even clasped his eyes upon wine in years. Where it once rushed through the streets of Ispahan, as cask after cask was filled and emptied, the streets now ran dry of it. There was still drops of it in the city he was sure, locked away in palaces with deep cellars and opened on the decadent nights after the amirs starved by day. For ayyarun, who were told to be above such sinfulness, who were to represent themselves in the land of honor, the bottles closed to them forever.

“I had thought as much.” Mazyar turned away for a breath, and then righted himself again. “A shame; I could never sleep without it.” Bahram knew not from his mind but from his heart that Mazyar lied then. These two souls, one a traitor and one a commoner, remembered their calling in the same manner, and lay together sleepless, ever staring at the perfidious face of the moon. Mazyar put his hand to his face, observing intensely all the features of Bahram. “I know what it is you are intending.”

“Do not stop me,” Bahram said. It was a pleading whisper, no louder than the wind, but it broke the ambience like the roar of the Dahag. It was the truth, and now that it had been spoken, the viciousness of it ate him up. There was no shame in death as there was in life, living to prostrate, living to wait. He was trapped on this side of the world, and great Mardavij on the other, the barrier that separated them as strong as he was weak. He could no longer imagine how an eternal sleep would be any worse than an eternal awakeness, for in that sleep he could yet dream of days he has never lived, of victories he has never won, of silver crowns and the sea and nothing in between them. It was the ultimate lie, one so devious that even he could himself believe it, that it would be so simple just to strike down the barrier and once again be reunited with his Shahanshah. Mazyar eventually waved his hand dismissively, blinking a long, slow blink that almost seemed to chase the fatigue from his eyes.

“That I would see you like this,” he muttered. Bahram nodded, and they at last kissed each other upon the cheek once, parting as brothers, as equals again. Alone once more, he ambled in a half-daze, through the quiet streets of Ispahan, along thin roads that led between houses, boxed together tight as Immortals. Before him he could only see one thing; the sheer face of the great Soffeh, that looked over the city as a watchful sentinel. Imposing as a mother, it judges him sternly, but he is now beyond judging. He continues on, stopping little, drinking nothing. He does not think about the wear upon his body, or of the needling sensation in his lungs. All he sees is the peak so far ahead of him, that beckons him up after a long five years of silence.

To behold as Hormazd did seemed to change everything. The world was smaller, somehow, when it was looked down upon. Ispahan, which in Mardavij’s time was the center of the world, was but a town, when faced against the majesty of the sky that dwarfed it. The many thriving souls living within could not match the rank of the stars, innumerable and each more brilliant than the wisest of philosophers. Had Mazdak, Vishtaspa, or Hushtana, wisest of those who had ever lived, come to have seen them as Bahram did, they would tear their papyrus into a thousand pieces and forget their pretensions to wisdom before the host of the solar magi. To think Hormazd above could stand to watch the sun rise upon this miniscule city for centuries, even while it was growing from the first Persians. Kourush would lament his mere mortality, for although he ruled the world entire, above him the stars still roamed free of his law. A sight fitting to be the last.

There, before him, the sky brightened, the stars retreating to make way for the first light of dawn. The sky in the east bloomed silver, in a circle about the horizon. A silver crown. The wind rose, and Bahram at last recalled a fond memory. He was here once before, eight years ago, as the Persian army stormed the walls, driving out the garrison of the Muqtadir Caliph. His horse stood idle, a shame he thought he at the time he would not forget, when behind him approached the Saoshyant, who stole away from the battle moments before his victory.

“I knew one had been missing,” Mardavij had said, and when Bahram twisted his hips to face the approaching rider, Mardavij had leaned forward and planted a kiss upon his lips. Bahram must have made a face, for Mardavij then laughed. “Why do you freeze so? If the Arab were to kiss you in battle, he shall as well as wear your head as a diadem!” He reached out with a hand and patted Bahram on his rounded shoulder. “Come; ride with me today, and I shall give you a share of the victories. The salar will be none the wiser; you were with me.” As master and servant, they descended the mountain, racing side by side towards their prize conquest. In that moment, Bahram found within himself a shred of the bravery he needed.

“I follow you five years too late, Saoshyant, forgive my absence,” Bahram whispered to the sun.

And he leapt.